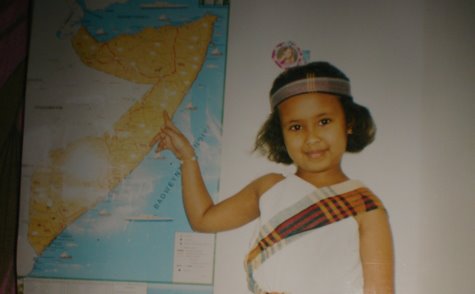

A Nomadic experience 1

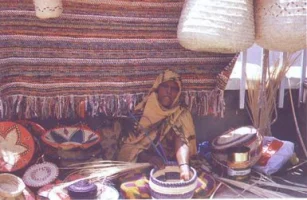

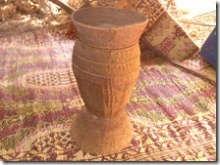

I woke up from my sisters hut. Beside me, stacked in some corner or hanging from the boughs were Sati, Sallad, Bocor, Hadhuub, dhiil, etc. – the very finest of a Somali nomad’s handmade utensils (I will explain these in another post hopefully in detail). Being my first time sleeping on a mat on rock solid earth, after so many years, together with my peculiar habit of sleeping on one side, I woke up with that morning with sore shoulders and a bruised ribcage.

It was a bright day, with a clear blue sky above. Not a single cloud hovered in the sky. The villagers of Habarshiro had already woken up and were by now at the wells, watering huge numbers of animals. My mother sat outside the hut – ardaaga, a partly enclosed area at the entrance of the hut plastered with tiny pebbles and covered (usually) with a mat – and made breakfast. That day it was Ruub – special thick round bread baked under burning ashes served with Sixin. After gobbling down the food quickly I made my way to the berked, for I have been informed that my younger sister, Zainab, would be arriving to see me today. I watered the animals from the Berked, all the time expecting the figure of my sister to emerge from behind the small hill that surrounds the village. After about an hour, she finally emerged, exhausted but with a radiant smile and with her seven-month old baby on her back! I couldn’t believe it – she had walked from a distance of four hours to come and see me and there were no words, however lofty, to repay that kind of love…

By noon, after we had lunch, I was sitting amidst several of my relatives when we were informed that a she-camel belonging to my father had gone missing a few days ago. The news came as a bolt from the blue to all the people, for their love for camels is without comparison. Generally, for the nomads, the lost camel is far dearer to them than all the present ones combined, so they would do everything at their disposal to search for it, often hunting it for days in the wilderness without returning home. Soon my brother, Mohamed, an expert camel herder, was sent with information of its last known location to follow it and bring back any news or sightings – a confirmation whether it was worth the pursuit or if it has been disposed of by the ever present predator, the hyena. They wanted a confirmation and as the old proverb goes “hubsiimo hal baa la siistaa” (precision/certainty is worth a she-camel). The rest of the day passed without much vibrancy.

The next morning my brother came early into the village with some news. Traditionally, when someone brings news to the nomads they welcome the bearer of the news in hope that he brings glad tidings. They say;

Warran oo lagugu ma warramo,

wiilkaaga mooyee walaalkaa ku ma dhaxlo,

la waari maayee waayo joog,

wax xun iyo cadaab la’ow

Bring news, but may your news not be brought

May your son inherit you and your brother not

Life won’t be long but may you live long

May you be free from all that is evil and hell

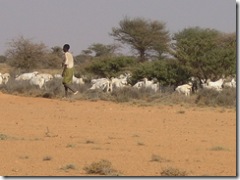

And he did bring some news. “There have been several sightings of a she-camel,” he said, “but its whereabouts were still unidentified. I have seen some tracks and followed them. There appeared to be a hyena chasing the camel, but just past Manshax the tracks disappeared.” The news was even worse than they had expected. The involvement of the hyena had raised their worst fears. Immediately an expedition was organised. The car that brought me to Habarshiro was still with me and so was the driver. It was then decided that we must take the car and look for the she-camel. We set off early, two of my brothers, my cousin and I, following tracks and trails of animals. Stopping at several huts yielded no valuable information. We finally met a young shephard in the vast Sool plateau and that’s when we were informed by the nomad that a ‘lone she-camel’ had been spotted earlier somewhere to our East. A sigh of relief came upon the faces of my brothers and cousin.

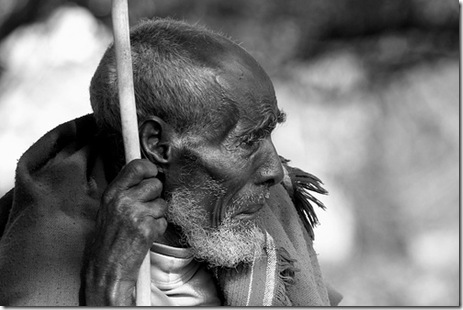

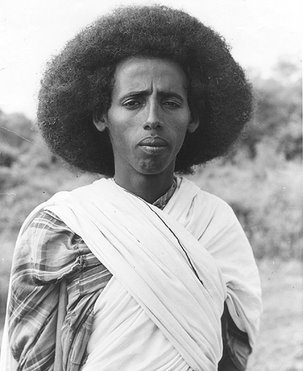

A nomad with his sheep and goats

We followed the direction of our informant nomad and headed east. The car drove slowly across plain fields and desiccated terrain, stopping from time to time and my brothers getting out to inspect and sift through the hundreds of footprints on the soil. Analysing the trails very precisely, they’d decide upon the time they were left and in which manner, as in if the camel was running or walking, and then they would decide upon the direction the tracks were leading to, thereby estimating a specific location that it would have reached.

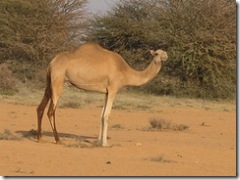

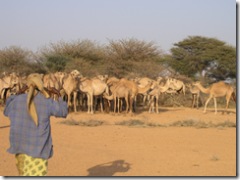

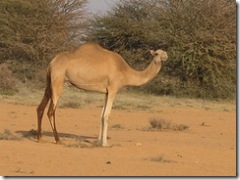

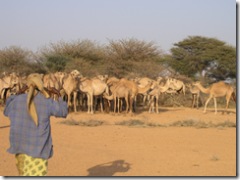

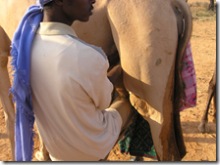

A camel-herder with his camels. This is my brother

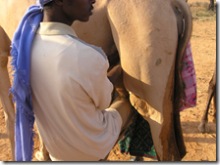

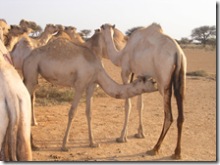

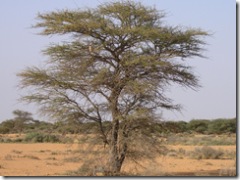

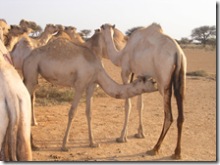

The nomads are expert trackers and their knowledge of their land is unrivalled. Using trees as landmarks and indicators of their location, the nomads know exactly how long it would take a camel, or a person for that matter, to travel from one place to another, and using this knowledge we headed for the probable route of the she-camel and the estimated destination. After about 2 hours, and regular intervals to inspect more tracks that would confirm our quest, we finally managed to find the she-camel, among other camels. She wasn’t in a bad state, except for her rear which was bitten by a hyena. This explained the running tracks that Mohamed saw on the first day of his inspection of the surrounding areas – the trails of the camel being chased. And what a relief it was. Such a relief that the camels were immediately milked and we were served with fresh camel milk with Ruub.

Milking a camel (haaneed) suckling her mother, though she is a bit old for that now.

As the days progressed, I learnt more about the customs of the Nomadic tribes and soon started to admire them. Though living in the throes of water shortages and meagre resources (this is during the dry seasons or Jiilaal. When it rains and water is in abundance, the nomads live a luxuriant life for they don’t have to take the animals to far away watering places and traditional songs and folk dances are performed regularly in the open. There is always plenty of meat and milk to be consumed and it becomes a merry time for weddings, so young men go scouting for their brides in these dances), the nomads are perhaps the one group of people who have understood life’s fundamental lesson of simplicity. They care neither for the trials the barren land may unfold tomorrow, nor do they weigh themselves down with the burdens of yesterday. They live for today, with as little of life’s encumbrances as possible. In their secluded world, detached from all worldly lures, the present is all that matters – the past has no relevance and the future no certainty. Enjoying whatever the earth yields, they live a frugal lifestyle without extravagance. They wake up the morning, each person going about his assigned job. No worries or stress, for as long as they have their camels, life is jolly good (except for the dry seasons when they struggle hard to find grazing grounds and water for their livestock).

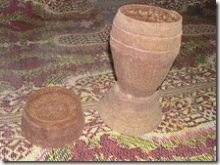

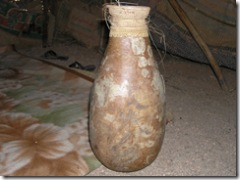

Eating Ruub with camel milk. What the man is holding is called Hadhuub-gaal or Gaawe

Now that I have returned to London, I have become slightly disenchanted with all the superfluous material pleasures and their impermanent value. Life in Miyi has left upon me an indelible impression and my wish is to return there as soon as chance permits me. I now have a clearer insight into the nomadic lifestyle with all its perils and pleasures. I do not think I could live it through though (settling down there I mean), but try I will one day!

The Somali Nomadic lifestyle is what defines the Somali culture. It is from these dry plateaus, valleys and watering holes from which all Somali traditions spring, forming the bedrock of the Somali society and a rich cultural heritage handed down to generations of camel herders and pastoralists. The traditional dances and weddings in Miyi forms the basis of almost all Somali poetry and music. To understand the meaning and origins of Somali poetry, music and literature, one must be fairly informed about the pastoral lifestyle, for without that one looses majority of the meanings, metaphors, allusions and insinuations imbedded within them.

The camel, as I have mentioned in an earlier post as well, is the centre of hundreds of poems from the earliest poets to the ones of today. Here is a poem that summarizes the life of the she-camel in 5 lines, from birth to maturity (I’ve added the ages the poet talks about for your convenience) ;

gugey dhalatay geed lagu xiryoo xariga loo gaabi

guga xigana gaaleemadiyo* dhogorta qaar goyso (2 jir)

guga xigana uur-giringiri* geela ku hor meedho (Qaalin yar, 3 jir)

guga xigana awar garabsatoo gooja* la hudeecdo (hal, 4 jir)

guga xigana good* nirig dhashay gaawe* laga buuxi (5 jir)

The year she was born, she is tied to a tree and the noose loosened

The year after that, she peels off part of her fur (age = 2)

The year after that, with a round belly, she parades in front of the camels (age = 3)

The year after that, she mates, becomes pregnant and dawdles (age = 4)

The year after that, good has given birth and a gaawe is filled (age = 5)

*Gaaleemada = the first fur the she-camel develops at a young age. this coat of fur stripped when the camel reaches about two years of age.

*uur-giringiri = by this time the calf develops a slightly big belly. She is neither suckling nor is she mature enough yet.

*Goojo = when the she-camel is pregnant the first sing is that as soon as someone approaches it, or a he-camel approaches it for mating, it spreads its hind legs and urinates. This is called Goojo and the camel-herder estimates a time when it would give birth.

*good = the she-camel is now called Good. As soon as she gives birth she is given a name, but before giving birth she is called “daughter of such and such” or “ina hebla”.

*Gaawe = Hadhuub gaal used for milking camels.

In another poem, Cumar Australia composed a brilliant poem about camels.

Ragga laxaha sii dhawrayow dhaqasho waa geele

Dhibaatiyo adoo gaajo qaba dhaxanta jiilaalka

Dhoor* caano laga soo lisoo yara dhanaanaaday

O’ you men who tend to sheep, rearing is camels

when adversity and hunger finds you in the winds of Jiilaal

The milk obtained from Dhoor with its sharp taste

Nin dhadhamiyey wuu garanayaa dhul ay qaboojaane

Goortaad dhantaa baa jidhkaba dhididku qooyaaye

Ragga laxaha sii dhawrayoow dhaqasho waa geele

A man who tasted them knows where they cool down

as soon as you drink it, does sweat drench the body

O’ you men who tend to sheep, rearing is camels

Waxa dhaba habeenkaa ninkii dhama galxoodkeeda*

Dhallaanimo qodxihii kugu mudnaa kaaga soo dhaca e

Ragga laxaha sii dhawrayoow dhaqasho waa geele.

Guaranteed it is that a man who drinks its (camels) Galax*

In childhood the thorns that pricked you would be discharged

O’ you men who tend to sheep, rearing is camels

*Galxood = comes from the word Galax. When a camel is milked, the fresh milk is initially hot and forms a lot of froth on the surface. The milk is left to settle down and the froth disappears. Once it disappears, very cold, pure milk is what remains. This is called Galax.

*Dhoor – Mane. Also known as Baar. A camel with a mane has not been used for carrying water or disassembled huts. Dhoor is also sometimes used as a name for a she-camel.

Cumar Australia also goes on to say that;

Inkastood adduun badan dhaqdo dheemman iyo daaro

Inkastood dhar wada suufa iyo dhag iyo laas qaaddo

Dhaxal male nin Soomaaliyoon dhaqannin koorreey*

despite having a world of diamond and dwellings

despite you having luxuriant clothes of cotton

Inheritence he has not, a Somali who doesn’t rear a camel

*koorreey = comes from the word Koor which means a wooden bell – the one tied around the camel’s neck. Here Koorey refers to camels.

For centuries the Somali Nomadic lifestyle had existed, people have endured the worst of droughts and famine and were content with their herd of camels, and though that lifestyle is now somewhat sluggishly diminishing, pastoralists will continue to exist despite the growing number of villages and urbanisation of Miyi.

cp.s I have attended a wedding in Miyi and will give you the details about the customs along with some pictures soon Insha-Allah.

Read Full Post »